Get into the flow

In Flow-Based Programming, programs are modeled as data flowing between independent processing units. Who would not think of channels and goroutines as a natural analogy?

Table of contents

As trivial as this may sound, all software is about processing data. Yet, when you look at code written in a “traditional” programming language, the actual data flow is not readily visible. Instead, what you mainly see are just the control structures. The actual data flow only happens to occur at runtime, as a consequence from the control structures.

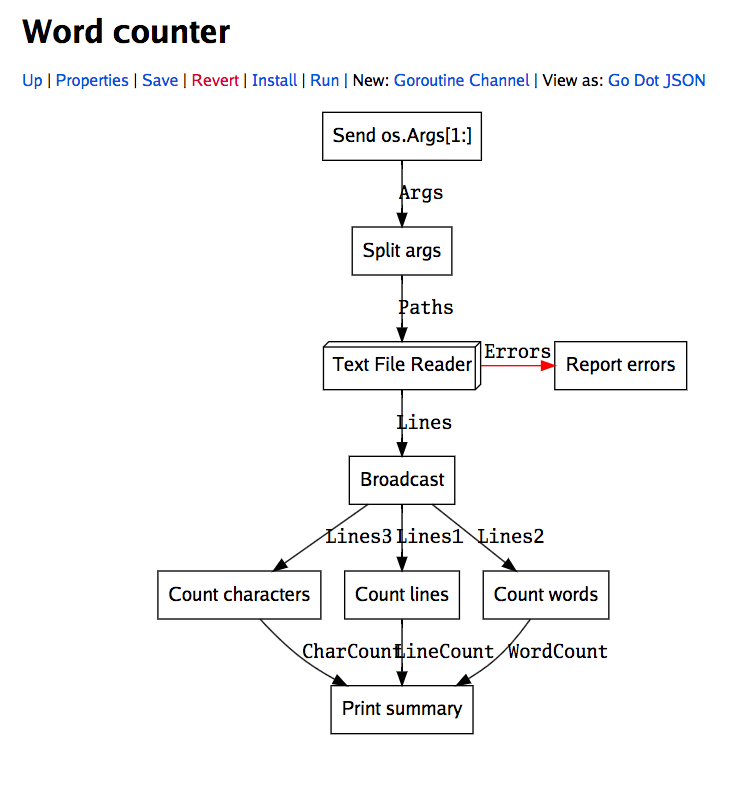

Flow-Based Programming (FBP) turns the view on code and data upside down. Here, the data flow is the first thing you look at; it is the main principle that defines the structure of your application. Processing of data happens within many small nodes that sit between the endpoints of data pipelines.

At this level, the processing nodes are just black boxes in a graphic flow diagram. The actual code hides within these boxes.

Flow-based programming and concurrency

Looking at an FBP diagram immediately raises two thoughts.

First, the data flow model is inherently concurrent. Data streams are independent of each other, and so are the nodes. Looks like optimal separation of concerns.

Second, a data flow looks darned close to channels and goroutines!

Do we have a natural match here? It seems tempting to build an FBP model directly on Go's built-in concurrency concepts.

In fact, this has been done already.

Go FBP libraries

A quick search on GitHub reveals a handful of Go-based FBP projects, which I list here together with their own descriptions.

trustmaster/goflow

“This is quite a minimalistic implementation of Flow-based programming and several other concurrent models in Go programming language that aims at designing applications as graphs of components which react to data that flows through the graph.”

scipipe/scipipe

“SciPipe is an experimental library for writing scientific Workflows in vanilla Go(lang). The architecture of SciPipe is based on an flow-based programming like pattern in pure Go (…)

flowbase/flowbase

“A Flow-based Programming (FBP) micro-framework for Go (Golang).”

ryanpeach/goflow

“A LabVIEW and TensorFlow Inspired Graph-Based Programming Environment for AI handled within the Go Programming Language.”

7ing/go-flow

“A cancellable concurrent pattern for Go programming language”

cascades-fbp/cascades

“Language-Agnostic Programming Framework for Data-Driven Applications”

themalkolm/go-fbp

“Go implementation of Flow-based programming.”

(The last one actually relies on input from a graphical FBP editor (DrawFBP) that it turns into code stubs.)

To be fair, some of these libs seem not actively maintained anymore. I included them anyway as there is no single true approach to this, and each of these libs shows a different approach and focuses on different aspects.

I also most certainly left out a few FBP libs that I failed to find in the short time of researching this topic, so feel free to do some more research on your own.

A simple FBP flow

For today's code, I picked the first of the libraries above, trustmaster/goflow. It provides a quite readable syntax and comes with detailed documentation. (On the flipside, goflow uses quite some reflection inside, which some of you might frown upon.)

Our sample code is an incarnation of the schematic FBP graph in the initial animation. Let's turn the abstract nodes and data items into someting more tangible. For example, we could feed the network with sentences and let one node count the words in each sentence and the other all letters. The final node then prints the results.

The code

First, we define the nodes. Each node is a struct with an embedded flow.Component and input and output channels (at least one of each kind, except for a sink node that only has input channels).

Nodes can act on input by functions that are named after the input channels. For example, if an input channel is named “Strings”, the function that triggers on new input is called “OnStrings” by convention.

We define these nodes:

- A splitter that takes the input and copies it to two outputs.

- A word counter that counts the words (i.e., non-whitespace content) of a sentence.

- A letter counter that counts the letters (a-z and A-Z) of a sentence.

- A printer that prints its input.

None of these nodes knows about any of the other nodes, and does not need to.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"regexp"

"strings"

flow "github.com/trustmaster/goflow"

)

counter nodes (see below) send their results asynchronously to the printer node. To distinguish between the outputs of the two counters, we attach a tag to each count. (Yes, sending just a string including the count would be easier but also more boring. The splitter already sends strings, so let's try something different here.)type count struct {

tag string

count int

}

splitter receives strings and copies each one to its two output ports.type splitter struct {

flow.Component

In <-chan string

Out1, Out2 chan<- string

}

OnIn dispatches the input string to the two output ports.func (t *splitter) OnIn(s string) {

t.Out1 <- s

t.Out2 <- s

}

WordCounter is a goflow component that counts the words in a string.type wordCounter struct {

flow.Component

Sentence <-chan string

Count chan<- *count

}

OnSentence triggers on new input from the Sentence port.

It counts the number of words in the sentence.func (wc *wordCounter) OnSentence(sentence string) {

wc.Count <- &count{"Words", len(strings.Split(sentence, " "))}

}

letterCounter is a goflow component that counts the letters in a string.type letterCounter struct {

flow.Component

Sentence <-chan string

Count chan<- *count

re *regexp.Regexp

}

OnSentence triggers on new input from the Sentence port.

It counts the number of words in the sentence.func (lc *letterCounter) OnSentence(sentence string) {

lc.Count <- &count{"Letters", len(lc.re.FindAllString(sentence, -1))}

}

Init method allows to initialize a component. Here we use it to run

the expensive MustCompile method once, rather than every time OnSentence is called.func (lc *letterCounter) Init() {

lc.re = regexp.MustCompile("[a-zA-Z]")

}

printer is a “sink” with no output channel. It prints the input

to the console.type printer struct {

flow.Component

Line <-chan *count // inport

}

OnLine prints a count.func (p *printer) OnLine(c *count) {

fmt.Println(c.tag+":", c.count)

}

CounterNet represents the complete network of nodes and data pipelines.type counterNet struct {

flow.Graph

}

Assembling the network

With the nodes in place, we can go foward and create the complete network, adding and connecting all the nodes.

func NewCounterNet() *counterNet {

n := &counterNet{}

n.InitGraphState()

&{}

instead of new.) Each node gets a name assigned that is used later

when connecting the nodes. n.Add(&splitter{}, "splitter")

n.Add(&wordCounter{}, "wordCounter")

n.Add(&letterCounter{}, "letterCounter")

n.Add(&printer{}, "printer")

n.Connect("splitter", "Out1", "wordCounter", "Sentence")

n.Connect("splitter", "Out2", "letterCounter", "Sentence")

n.Connect("wordCounter", "Count", "printer", "Line")

n.Connect("letterCounter", "Count", "printer", "Line")

splitter.In. n.MapInPort("In", "splitter", "In")

return n

}

Launching the network

Finally, we only need to activate the network, create an input port, and start feeding it with selected bits of wisdom.

func main() {

net := NewCounterNet()

in := make(chan string)

net.SetInPort("In", in)

flow.RunNet(net)

in <- "I never put off till tomorrow what I can do the day after."

in <- "Fashion is a form of ugliness so intolerable that we have to alter it every six months."

in <- "Life is too important to be taken seriously."

close(in)

<-net.Wait()

}

How to get and run the code

Step 1: go get the code. Note the -d flag that prevents auto-installing the binary into $GOPATH/bin.

go get -d github.com/appliedgo/flow

Step 2: cd to the source code directory.

cd $GOPATH/src/github.com/appliedgo/flow

Step 3. Run the binary.

go run flow.go

The output should look like:

Letters: 45

Words: 17

Words: 13

Letters: 36

Words: 8

Letters: 70

The unordered output shows that the nodes are indeed running asynchronously. Homework assignment: Add more info to the count struct to allow the printer node grouping the output by input sentence.

Conclusions

Still, although we were able to nicely describe our nodes and the connections between them, the resulting code is far from representing an intuitive view on the flow of data within the program. This should not be surprising. A textual representation rarely matches up with the intuitiveness of a graphic representation.

So where is the visual flow diagram editor, you ask?

There are indeed some options.

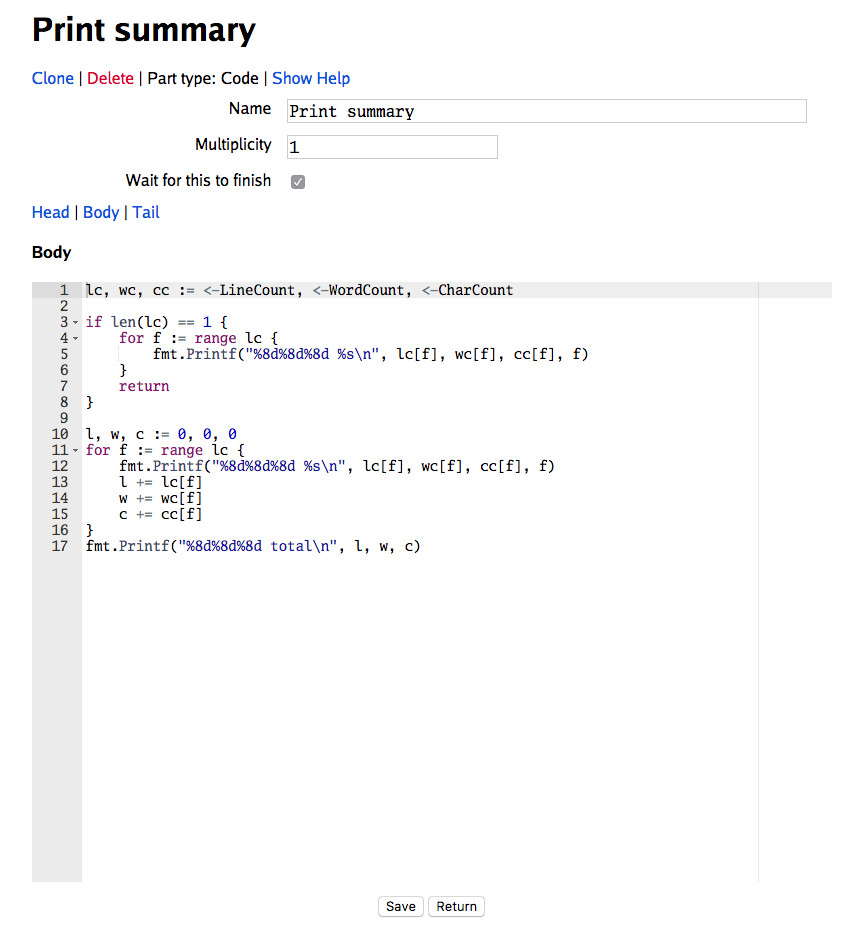

Shenzhen Go

Just recently, an experimental visual Go environment has been presented to the public - Shenzhen Go. (Careful though - “experimental” means exactly this.)

Some nodes contain configurable standard actions, others contain Go code that reads from input channels and writes to output channels (unless the node is a sink).

go-fbp and DrawFBP

If you want a graphic editor now and don't want to wait until Shenzhen Go is production ready, have a look at themalkolm/go-fbp. This project generates Go code from the output of a graphical FBP editor called DrawFBP (a Java app). (Disclaimer: I have tested neither go-fbp nor DrawFBP.)

Further Links

Wikipedia: Flow-based programming

John Paul Morrison: FBP flowbased.org

Gopheracademy: Patterns for composable concurrent pipelines in Go

Gopheracademy: Composable Pipelines Improved

Happy coding!

Updates

2022-01-08 pinned goflow to “v0” (commit 47a1b442f390) as “v1” has breaking changes