Message Queues Part 2: The PubSub Protocol

This is the second (and, for the time being, the last) article about messaging and Mangos. After doing first steps with the Pair protocol, we now look into a slightly more complex protocol, the Publisher-Subscriber (or PubSub) protocol.

The Publisher-Subscriber model in a nutshell

What is PubSub exactly?

PubSub is a communication topology where a single entity called Publisher produces messages that it sends out to other entities called Subscribers. Subscribers may receive everything the publisher sends, or they may subscribe to message subsets called Topics.

This sounds much like some news service sending articles out to readers, and in fact many news services work this way. Whether you subscribe to an RSS feed, to one or more forums on a discussions platform, or follow someone on Twitter–in each case, there is one publisher and multiple subscribers involved.

Where can a PubSub topology be used?

Typically, PubSub addresses scenarios like these:

- Multiple observers need to act upon status changes of a single entity.

- Multiple workers shall process data from a single entity. Results are not sent back to that entity.

Implementation variations

Subscription strategies can differ based on the system architecture.

- If the system has a broker, clients subscribe to the broker rather than to the server, and the broker takes care of routing the messages to the clients based on the subscribed topics.

- In brokerless systems, clients may either send their topics to the server, and the server then sends each message only to the clients that have subscribed for that topic.

- Or the clients filter the messages at their end. The server then simply sends all messages to all clients. (This approach is fine in smaller, local scenarios but does not scale well.)

How Mangos implements the PubSub protocol

As seen in the Pair example in the previous article, Mangos uses special, protocol-aware sockets. In a PubSub scenario, the “pub” socket just sends out its messages to all receivers (or to nirvana if no one is listening). The “sub” socket is able to filter the incoming messages by topic and only delivers the messages that match one of the subscribed topics.

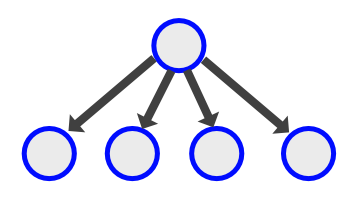

The animation below shows the Mangos approach - the publisher sends all messages to all subscribers, and the subscribers filter the messages according to the topics they have subscribed to:

This is certainly a rather simple and robust approach, as the server does not need to manage the clients and their subscriptions; on the downside, as noted above, filtering on client side does not scale well with the number of clients.

A PubSub example

Let’s dive into coding now. We’ll develop a tiny example where a couple of clients subscribe to a few topics, and the server then publishes some messages by topic.

But first, let’s do the installation stuff.

Installing Mangos and importing the packages

Like in the previous post, Mangos is installed via a simple go get:

go get -u github.com/go-mangos/mangos

Now you can import Mangos into your .go file.

The code

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"os"

"os/exec"

"time"

"github.com/go-mangos/mangos"

"github.com/go-mangos/mangos/protocol/pub"

"github.com/go-mangos/mangos/protocol/sub"

"github.com/go-mangos/mangos/transport/ipc"

"github.com/go-mangos/mangos/transport/tcp"

)

func newPublisherSocket(url string) (mangos.Socket, error) {

socket, err := pub.NewSocket()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

socket.AddTransport(ipc.NewTransport())

socket.AddTransport(tcp.NewTransport())

err = socket.Listen(url)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return socket, nil

}

func newSubscriberSocket(url string) (mangos.Socket, error) {

socket, err := sub.NewSocket()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

socket.AddTransport(ipc.NewTransport())

socket.AddTransport(tcp.NewTransport())

err = socket.Dial(url)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return socket, nil

}

func subscribe(socket mangos.Socket, topic string) error {

err := socket.SetOption(mangos.OptionSubscribe, []byte(topic))

if err == nil {

err = socket.SetOption(mangos.OptionRecvDeadline, 10*time.Second)

}

return err

}

|) separates the topic from the message. This is only done for better

readability. In ‘real’ scenarios, the receiver would just strip away the topic prefix and

pass the rest of the message over to the next processing stage.func publish(socket mangos.Socket, topic, message string) error {

err := socket.Send([]byte(fmt.Sprintf("%s|%s", topic, message)))

return err

}

func receive(socket mangos.Socket) (string, error) {

message, err := socket.Recv()

return string(message), err

}

func runServer(url string, topics []string) {

socket, err := newPublisherSocket(url)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Cannot listen on %s: %s\n", url, err.Error())

}

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

for _, topic := range topics {

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("Publishing a message for topic %s\n", topic)

err = publish(socket, topic, fmt.Sprintf("Message for %s", topic))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Cannot publish message for topic %s: %s\n", topic, err.Error())

}

}

}

}

func runClient(name, url string, topics []string) {

socket, err := newSubscriberSocket(url)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Cannot dial into %s: %s\n", url, err.Error())

}

for _, topic := range topics {

err := subscribe(socket, topic)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Cannot subscribe to topic %s: %s\n", topic, err.Error())

}

}

for i := 0; i < 5*len(topics); i++ {

message, err := receive(socket)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Error receiving message: %s\n", err.Error())

}

fmt.Printf("Client %s received: %s\n", name, message)

}

}

func main() {

url := "tcp://localhost:56565"

if len(os.Args) == 1 {

Cmd type from the os.exec package to spawn the clients

as subprocesses in a convenient way. client1 := exec.Command("./pubsub", "C1", "Technology")

client1.Stdout = os.Stdout // Default is nil but we want to see what the clients say.

client1.Stderr = os.Stderr // Same here.

client2 := exec.Command("./pubsub", "C2", "Technology", "Weather")

client2.Stdout = os.Stdout

client2.Stderr = os.Stderr

client3 := exec.Command("./pubsub", "C3", "Finance")

client3.Stdout = os.Stdout

client3.Stderr = os.Stderr

fmt.Println("Starting client 1")

err := client1.Start() // Start the command and continue without waiting for the command to finish.

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed starting client1: %s", err.Error())

}

fmt.Println("Starting client 2")

err = client2.Start()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed starting client2: %s", err.Error())

}

fmt.Println("Starting client 3")

err = client3.Start()

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("Failed starting client3: %s", err.Error())

}

fmt.Println("Starting the server")

runServer(url, []string{"Technology", "Weather", "Finance"})

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second) // to ensure all clients have consumed the messages.

fmt.Println("Waiting for the clients to exit")

client1.Wait()

client2.Wait()

client2.Wait()

fmt.Println("Server ends.")

} else {

fmt.Println(os.Args[1], "is starting.")

runClient(os.Args[1], url, os.Args[2:])

fmt.Println("Client", os.Args[1], "ends.")

}

}

Get this code from github:

go get -d github.com/appliedgo/pubsub

cd $GOPATH/src/github.com/appliedgo/pubsub

go build

./pubsub

(go get -d gets the code but does not install it into $GOPATH/bin. go build then builds the executable locally so that it would not end up between your other executables, especially if $GOPATH/bin is part of your $PATH.)

As you have seen in the code for main(), the program spawns three child processes that take over the role of the clients. If everything works fine, you should then see the publisher send 15 messages to the clients, and the clients should then grab only the messages that they have subscribed to.

For additional fun, try tweaking some parameters. For example, comment out the last time.Sleep() statement in main(). Or have the clients expect more messages than the server sends, and see what happens!

Have fun!

Globals and imports