Balancing a binary search tree

Only a well-balanced search tree can provide optimal search performance. This article adds automatic balancing to the binary search tree from the previous article.

Table of contents

Get the Balance Right!

~ Depeche Mode

How a tree can get out of balance

As we have seen in last week's article, search performance is best if the tree's height is small. Unfortunately, without any further measure, our simple binary search tree can quickly get out of shape - or never reach a good shape in the first place.

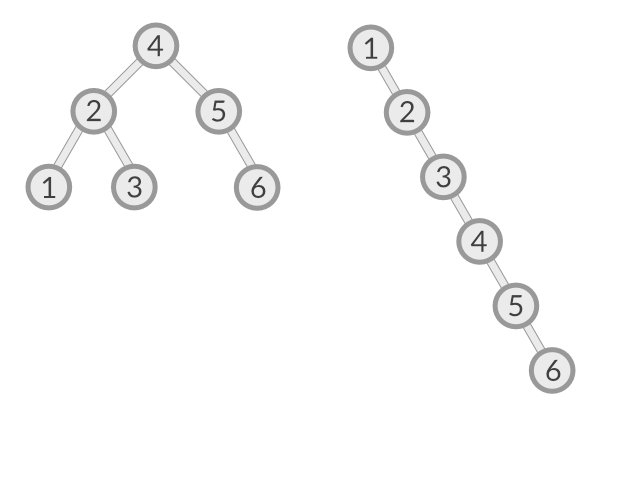

The picture below shows a balanced tree on the left and an extreme case of an unbalanced tree at the right. In the balanced tree, element #6 can be reached in three steps, whereas in the extremely unbalanced case, it takes six steps to find element #6.

Unfortunately, the extreme case can occur quite easily: Just create the tree from a sorted list.

tree.Insert(1)

tree.Insert(2)

tree.Insert(3)

tree.Insert(4)

tree.Insert(5)

tree.Insert(6)

According to Insert’s logic, each new element is added as the right child of the rightmost node, because it is larger than any of the elements that were already inserted.

We need a way to avoid this.

A Definition Of “Balanced”

For our purposes, a good working definition of “balanced” is:

The heights of the two child subtrees of any node differ by at most one.

(Wikipedia: AVL-Tree)

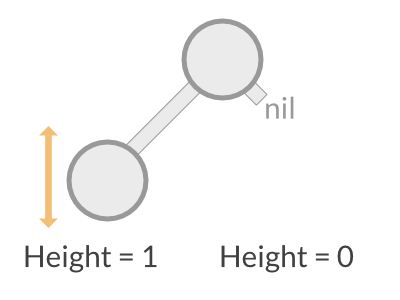

Why “at most one”? Shouldn't we demand zero difference for perfect balance? Actually, no, as we can see on this very simple two-node tree:

The left subtree is a single node, hence the height is 1, and the right “subtree” is empty, hence the height is zero. There is no way to make both subtrees exactly the same height, except perhaps by adding a third “fake” node that has no other purpose of providing perfect balance. But we would gain nothing from this, so a height difference of 1 is perfectly acceptable.

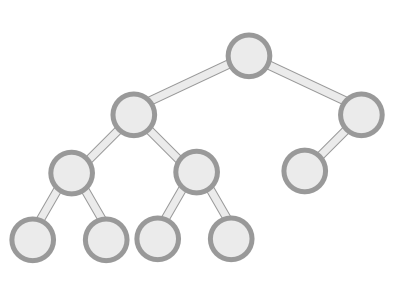

Note that our definition of balanced does not include the size of the left and right subtrees of a node. That is, the following tree is completely fine:

The left subtree is considerably larger than the right one; yet for either of the two subtrees, any node can be reached with at most four search steps. And the heights of both subtrees differs only by one.

How to keep a tree in balance

Now that we know what balance means, we need to take care of always keeping the tree in balance. This task consists of two parts: First, we need to be able to detect when a (sub-)tree goes out of balance. And second, we need a way to rearrange the nodes so that the tree is in balance again.

Step 1. Detecting an imbalance

Balance is related to subtree heights, so we might think of writing a “height” method that descends a given subtree to calculate its height. But this can be come quite costly in terms of CPU time, as these calculations would need to be done repeatedly as we try to determine the balance of each subtee and each subtree's subree, and so on.

Instead, we store a “balance factor” in each node. This factor is an integer that tells the height difference between the node's right and left subtrees, or more formally (this is just maths, no Go code):

balance_factor := height(right_subtree) - height(left_subtree)

Based on our definition of “balanced”, the balance factor of a balanced tree can be -1, 0, or +1. If the balance factor is outside that range (that is, either smaller than -1 or larger than +1), the tree is out of balance and needs to be rebalanced.

After inserting or deleting a node, the balance factors of all affected nodes and parent nodes must be updated.

For brevity, this article only handles the Insert case.

Here is how Insert maintains the balance factors:

- First,

Insertdescends recursively down the tree until it finds a nodento append the new value.nis either a leaf (that is, it has no children) or a half-leaf (that is, it has exactly one (direct) child). - If

nis a leaf, adding a new child node increases the height of the subtreenby 1. If the child node is added to the left, the balance ofnchanges from 0 to -1. If the child is added to the right, the balance changes from 0 to 1. Insertnow adds a new child node to noden.- The height increase is passed back to

n’s parent node. - Depending on whether

nis the left or the right child, the parent node adjusts its balance accordingly.

If the balance factor of a node changes to +2 or -2, respectively, we have detected an imbalance. At this point, the tree needs rebalancing.

Removing the imbalance

Let's assume a node n that has one left child and no right child. n’s left child has no children; otherwise, the tree at node n would already be out of balance. (The following considerations also apply to inserting below the right child in a mirror-reversed way, so we can focus on the left-child scenario here.)

Now let's insert a new node below the left child of n.

Two scenarios can happen:

1. The new node was inserted as the left child of n’s left child.

Since n has no right children, its balance factor is now -2. (Remember, the balance is defined as “height of right tree minus height of left tree”.)

This is an easy case. All we have to do is to “rotate” the tree:

- Make the left child node the root node.

- Make the former root node the new root node's right child.

Here is a visualization of these steps (click “Rotate”):

The balance is restored, and the tree's sort order is still intact.

Easy enough, isn't it? Well, only until we look into the other scenario…

2. The new node was inserted as the right child of n’s left child.

This looks quite similar to the previous case, so let's try the same rotation here. Click “Single Rotation” in the diagram below and see what happens:

The tree is again unbalanced; the root node's balance factor changed from -2 to +2. Obviously, a simple rotation as in case 1 does not work here.

Now try the second button, “Double Rotation”. Here, the unbalanced node's left subtree is rotated first, and now the situation is similar to case 1. Rotating the tree to the right finally rebalances the tree and retains the sort order.

Two more cases and a summary

The two cases above assumed that the unbalanced node's balance factor is -2. If the balance factor is +2, the same two cases apply in an analogous way, except that everything is mirror-reversed.

To summarize, here is a scenario where all of the above is included - double rotation as well as reassigning a child node/tree to a rotated node.

The Code

Update: a version of this code using type parameters (a.k.a generics) is available in the article How I turned a binary search tree into a generic data structure with go2go · Applied Go

Now, after all this theory, let's see how to add the balancing into the code from the previous article.

First, we set up two helper functions, min and max, that we will need later.

Imports, helper functions, and globals

package main

import ( “fmt” “strings” )

func min(a, b int) int {

if a < b {

return a

}

return b

}

max is math.Max for int.func max(a, b int) int {

if a > b {

return a

}

return b

}

Node gets a new field, height, to store the height of the subtree at this node.type Node struct {

Value string

Data string

Left *Node

Right *Node

height int

}

*Node is nil. If a child node is nil, there is no heightfield available; however, it is possible to call a method of a nil struct value!

As a Go proverb says, “Make the zero value useful”.func (n *Node) Height() int {

if n == nil {

return 0

}

return n.height

}

func (n *Node) Bal() int {

return n.Right.Height() - n.Left.Height()

}

The modified Insert function

Insert takes a search value and some data and inserts a new node (unless a node with the given

search value already exists, in which case Insert only replaces the data).It returns:

trueif the height of the tree has increased.falseotherwise.

func (n *Node) Insert(value, data string) *Node {

if n == nil {

return &Node{

Value: value,

Data: data,

height: 1,

}

}

if n.Value == value {

n.Data = data

return n

}

if value < n.Value {

n.Left = n.Left.Insert(value, data)

} else {

n.Right = n.Right.Insert(value, data)

}

n.height = max(n.Left.Height(), n.Right.Height()) + 1

n might be out of balance. return n.rebalance()

}

The new rebalance() method and its helpers rotateLeft(), rotateRight(), rotateLeftRight(), and rotateRightLeft.

Important note: Many of the assumptions about balances, left and right children, etc, as well as much of the logic usde in the functions below, apply to the Insert operation only. For Delete operations, different rules and operations apply. As noted earlier, this article focuses on Insert only, to keep the code short and clear.

rotateLeft rotates the node to the left.func (n *Node) rotateLeft() *Node {

fmt.Println("rotateLeft " + n.Value)

n’s right child in r. r := n.Right

r’s right subtree to the left of n. n.Right = r.Left

n the left child of r. r.Left = n

n.height = max(n.Left.Height(), n.Right.Height()) + 1

r.height = max(r.Left.Height(), r.Right.Height()) + 1

return r

}

rotateRight is the mirrored version of rotateLeft.func (n *Node) rotateRight() *Node {

fmt.Println("rotateRight " + n.Value)

l := n.Left

n.Left = l.Right

l.Right = n

n.height = max(n.Left.Height(), n.Right.Height()) + 1

l.height = max(l.Left.Height(), l.Right.Height()) + 1

return l

}

rotateRightLeft first rotates the right child of c to the right, then c to the left.func (n *Node) rotateRightLeft() *Node {

n.Right = n.Right.rotateRight()

n = n.rotateLeft()

n.height = max(n.Left.Height(), n.Right.Height()) + 1

return n

}

rotateLeftRight first rotates the left child of c to the left, then c to the right.func (n *Node) rotateLeftRight() *Node {

n.Left = n.Left.rotateLeft()

n = n.rotateRight()

n.height = max(n.Left.Height(), n.Right.Height()) + 1

return n

}

rebalance brings the (sub-)tree with root node c back into a balanced state.func (n *Node) rebalance() *Node {

fmt.Println("rebalance " + n.Value)

n.Dump(0, "")

switch {

case n.Bal() < -1 && n.Left.Bal() == -1:

return n.rotateRight()

case n.Bal() > 1 && n.Right.Bal() == 1:

return n.rotateLeft()

case n.Bal() < -1 && n.Left.Bal() == 1:

return n.rotateLeftRight()

case n.Bal() > 1 && n.Right.Bal() == -1:

return n.rotateRightLeft()

}

return n

}

Find stays the same as in the previous article.func (n *Node) Find(s string) (string, bool) {

if n == nil {

return "", false

}

switch {

case s == n.Value:

return n.Data, true

case s < n.Value:

return n.Left.Find(s)

default:

return n.Right.Find(s)

}

}

Dump dumps the structure of the subtree starting at node n, including node search values and balance factors.

Parameter i sets the line indent. lr is a prefix denoting the left or the right child, respectively.func (n *Node) Dump(i int, lr string) {

if n == nil {

return

}

indent := ""

if i > 0 {

indent = strings.Repeat(" ", (i-1)*4) + "+" + lr + "--"

}

fmt.Printf("%s%s[%d,%d]\n", indent, n.Value, n.Bal(), n.Height())

n.Left.Dump(i+1, "L")

n.Right.Dump(i+1, "R")

}

Tree

Changes to the Tree type:

Insertnow takes care of rebalancing the root node if necessary.- A new method,

Dump, exist for invokingNode.Dump. Deleteis gone.

type Tree struct { Root *Node }

func (t *Tree) Insert(value, data string) { t.Root = t.Root.Insert(value, data)

if t.Root.Bal() < -1 || t.Root.Bal() > 1 {

t.rebalance()

}

}

Node’s rebalance method is invoked from the parent node of the node that needs rebalancing.

However, the root node of a tree has no parent node.

Therefore, Tree’s rebalance method creates a fake parent node for rebalancing the root node.func (t *Tree) rebalance() {

if t == nil || t.Root == nil {

return

}

t.Root = t.Root.rebalance()

}

func (t *Tree) Find(s string) (string, bool) {

if t.Root == nil {

return "", false

}

return t.Root.Find(s)

}

func (t *Tree) Traverse(n *Node, f func(*Node)) {

if n == nil {

return

}

t.Traverse(n.Left, f)

f(n)

t.Traverse(n.Right, f)

}

func (t *Tree) PrettyPrint() {

printNode := func(n *Node, depth int) {

fmt.Printf("%s%s\n", strings.Repeat(" ", depth), n.Value)

}

walk has to be declared explicitly. Otherwise the recursive

walk() calls inside walk would not compile. var walk func(*Node, int)

walk = func(n *Node, depth int) {

if n == nil {

return

}

walk(n.Right, depth+1)

printNode(n, depth)

walk(n.Left, depth+1)

}

walk(t.Root, 0)

}

Dump dumps the tree structure.func (t *Tree) Dump() {

t.Root.Dump(0, "")

}

A demo

Using the Dump method plus some fmt.Print... statements at relevant places, we can watch the code how it inserts new values, rebalancing the subtrees where necessary.

The output of the final Dump call should look like this:

g[1]

+L--d[0]

+L--b[0]

+L--a[0]

+R--c[0]

+R--e[1]

+R--f[0]

+R--i[1]

+L--h[0]

+R--k[0]

+L--j[0]

+R--l[0]

The small letters are the search values. “L” and “R” denote if the child node is a left or a right child. The number in brackets is the balance factor.

If everything works correctly, the Traverse method should finally print out the nodes in alphabetical sort order.

func main() {

values := []string{"d", "b", "g", "g", "c", "e", "a", "h", "f", "i", "j", "l", "k"}

data := []string{"delta", "bravo", "golang", "golf", "charlie", "echo", "alpha", "hotel", "foxtrot", "india", "juliett", "lima", "kilo"}

tree := &Tree{}

for i := 0; i < len(values); i++ {

fmt.Println("Insert " + values[i] + ": " + data[i])

tree.Insert(values[i], data[i])

tree.Dump()

fmt.Println()

}

fmt.Print("Sorted values: | ")

tree.Traverse(tree.Root, func(n *Node) { fmt.Print(n.Value, ": ", n.Data, " | ") })

fmt.Println()

fmt.Println("Pretty print (turned 90° anti-clockwise):")

tree.PrettyPrint()

}

As always, the code is available on GitHub. Using the -d flag with go get to avoid that the binary gets auto-installed into $GOPATH/bin.

go get -d github.com/appliedgo/balancedtree

cd $GOPATH/src/github.com/appliedgo/balancedtree

go build

./balancedtree

The code is also available on the Go Playground. (Subject to availabilty of the Playground service.)

Conclusion

Keeping a binary search tree in balance is a bit more involved as it might seem at first. In this article, I have broken down the rebalancing to the bare minimum by removing the Delete operation entirely. If you want to dig deeper, here are a couple of useful readings:

Wikipedia on Tree Rotation: Richly illustrated, concise discussion of the rotation process.

German Wikipedia on AVL Trees: Sorry, this is German only, but when you scroll down to section 4, “Rebalancierung”, there are a couple of detailed diagrams on single and double rotation. Here you can see how the subtree heights change after each rotation.

GitHub search for Go AVL libs: For advanced study :)

That's it. Happy tree planting!

Changelog

2021-06-18 fix issue #2 and streamline the code

minis like math.Min but for int.